“Nothing in the upper world can compare with the luxury of this nether realm of the sea, with its colors, its atmosphere of mystery, of poise, and tranquility.”

“Contemplating the teeming life of the shore,” the poetic marine biologist Rachel Carson wrote as she reckoned with the ocean and the meaning of life, “we have an uneasy sense of the communication of some universal truth that lies just beyond our grasp… the ultimate mystery of Life itself.” Fifteen years earlier, she had invited the human imagination into the wonders of the underwater world — a world then more mysterious than the Moon — in an unexampled essay that later bloomed into her 1951 book The Sea Around UsShe was the National Book Award winner for her book, and is considered the best-known science writer in the world.

Carson dedicated the book to the pioneering explorer, marine biologist, ornithologist, and Wildlife Conservation Society naturalist William Beebe, who had gone deeper than any human had gone before in his epoch-making 1930s dives in the Bathysphere — the spherical submersible Beebe dreamt up with the deep-sea diver and engineer Otis Barton, his sole companion inside the miniature globe reaching for the bottom of the world.

It had only been a generation since the German oceanographer Carl Chun’s pioneering Valdiva expedition had emerged with stunningly illustrated evidence defying humanity’s shallow imagination, which had long deemed life below 300 fathoms impossible. The wonders of the world are endless. Valdiva saw, it could not escape the blind spots of its epoch — the creatures it discovered were abducted from their underwater homes and dredged up for the scientists to study on the surface, lifeless.

The Bathysphere reined in a new era of closer and more compassionate study, making Beebe the first scientist to observe deep-sea wildlife in their habitat, unharmed in their alien aliveness, moving silent and splendid amid a world he saw as “stranger than any imagination could have conceived,” irradiated by an “indefinable translucent blue quite unlike anything” known in the upper world.

Beebe celebrated his return from the Bathysphere’s first dive in 1930 when he flipped on the pages. New York Zoological Society Bulletin:

Under a tremendous pressure, which if released in a split second could make the amorphous tissues of a human body, I felt privileged to be able to see through limited eyes and to interpret with a mind completely unsuited to this task.

Beebe, despite his poetic gift for language, knew that words would only go so far to convey the wonder and complexity of the underwater world to people whose eyes could not see it or whose imaginations were still too limited to comprehend it.

“Adequate presentation of what I saw on these dives is one of the most difficult things I ever attempted,” he reflected, likening the splendid irreducibility of it all to that of asking a foreigner who has spent a few hours in New York City to describe America.

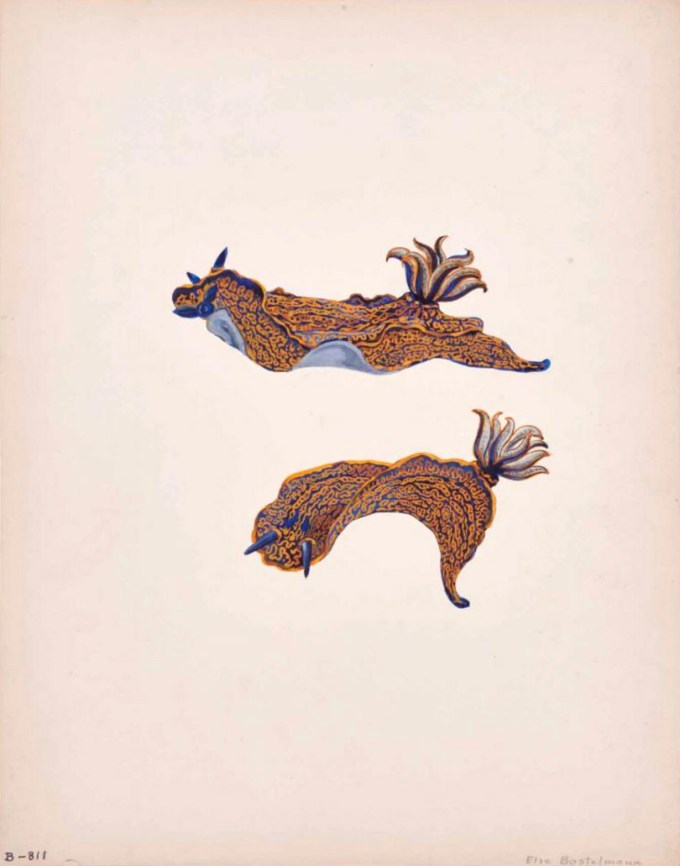

A century after Walt Whitman imagined the “wars, pursuits, tribes, sight in those ocean-depths” of the unimaginable “world below the brine,” what opened the terrestrial imagination to the realities of that unseen and unfathomed world was the artwork of Else Bolstelmann (1882–1961) — some of it preserved in the Wildlife Conservation Society’s wonderful digital collections and featured in a Drawing Center exhibition; some, along with her surviving papers, brought to light by oceanographer Edith Widder in her heroic resuscitation of Bostelmann’s forgotten story; some hunted down and restored in my own dives into out-of-print publications and antiquarian collections.

Born in Germany, where she was already an established artist before marrying an American cellist and emigrating to New York in her late twenties, Bostelmann was approaching fifty when she heard that the National Geographic Society was sponsoring a trailblazing oceanographic expedition to explore the wonders of the deep, launching from Beebe’s research station off the coast of Bermuda’s marvelously named Nonsuch Island.

After being a widowed mother for almost ten years, she was determined to use her artistic talent of beauty to help our quest for scientific truth. She contacted Beebe through the New York Zoological Society, Bronx Zoo. Beebe offered her talents and time. Beebe — who believed in the power of the fine arts to render the mysteries of nature and the abstractions of science real — was instantly taken with her exuberant precision, with the striking colors emanating from an unfaltering fidelity to form, and hired her as scientific artist for the expedition.

Else Bostelmann created more than 300 plates featuring marine animals in Bermuda. Many of these creatures were previously unknown to human eyes. Bostelmann, a Dutch atlas-maker and engraver who gave the world half-imagined fantasal fishes in the first marine encyclopedia illustrated with color, brought the reality to life two centuries later.

Astonishingly, Bostelmann never submerged in the Bathysphere herself — she later recalled that because she was the single mother of a teenage daughter, Beebe could not bring himself to put her in danger. It is not unreasonable to be concerned that the Bathysphere was filled with water after one of the test submersions went wrong.

Going only by Beebe’s verbal descriptions, dictated from the underwater wonderland via a telephone line inside the hose by which the Bathysphere dangled from the ship, she became the marine biologist’s prosthetic eye, a human periscope in reverse, bringing to life the strange and wondrous creatures of the deep — flying snails and whiskered shrimp and saber-toothed fish — in watercolor, gouache, and pencil.

Upon his return to the surface, Beebe recalled that the two of them would go into an “artistic huddle” and slowly refine the “proportions, size, color, lights,” and other details of his “brain fish,” integrating his memory of the sight with the artwork, until a “splendid finished painting” emerged.

Spiked and tentacled and bioluminescent, monstrous and magical with their prehistoric jaws and their otherworldly colors, Bostelmann and Beebe’s co-created creatures peer out of her paintings with their perpetually wonder-stricken lidless eyes and ever-hungry mouths. They were given the following titles: Big Bad Wolves of an Abyssal Chamber of HorrorsThe saber-toothed viperfish was a favorite of hers. As an imagist of deep sublime, she loved their weirdness and incredible monstrosity.

Illustrating Beebe’s books and essays for the general public, and paying for her daughter’s education, Bostelmann’s artwork made its way into magazines and museums, into National GeographicNew York Academy of Sciences. These scientists have inspired generations of scientists. They also awaken millions of everyday people to the otherworldly enchantments of the planet.

In an era when women — including trained scientists like Carson — were still not allowed on government research vessels, Bostelmann was one of several female artists and scientific collaborators who accompanied Beebe on his expeditions. That Beebe — widely remembered as a man of warmhearted sincerity and generosity of spirit — put women in leadership positions no doubt speaks to his values, an epoch ahead of his era. But he was also a pragmatist — in assembling his team, he sought “adaptable scientific students” willing to go along with his daring ideas and he found that women often had those qualities. When Theodore Roosevelt visited Beebe’s “little party of naturalists,” he found them partaking of that “rare combination of working had at a task in which their souls delighted, and also taking part in a thrilling kind of picnic.” Science, at its best, is indeed just that — a feast of knowledge on a flying picnic-blanket of wonder.

But as much as Bostelmann cherished her rare access to the world’s unseen wonders, she could not reconcile this reverie for the grandeur of life with the cruelties of science, as commonly practiced in her day. The animals she drew from “specimens” ranged from smaller than a pea to longer than a foot — each a “mythic creature drawn up from the murky, unexplored depths of the ocean,” each revealing “a new world of undreamt beauty” under the microscope, yet each robbed of life on the way to her desk. As she watched them emerge from the rose-tinted waters in the trawl nets at sunset, she sorrowed for the “little captives” and eulogized their lot with uncommon compassion. More than half a century before Thomas Nagel’s classic What is it like to be a bat challenged our human consciousness — and conscience — to imagine the creaturely experience of creatures radically unlike us but also aglow with sentience and sensitivity, Bostelmann wrote:

They have traveled a long way to reach my table, and far from the eternal night where they used to live, have discovered a new home. They were pulled behind the bow of a tugboat by a long silk net. There was no escape from the net, and there were also no Mason jars at the end. Thus, from the depths of an everlasting night — about 1000 fathoms — and an ice cold temperature, through an enormous change of pressure, they had been drawn up into a sun-flooded world where they could not possibly adjust themselves. These were the reasons why they died before I could save them.

So she chose to take inspiration from the sea, where all life lives.

Although Bostelmann never submerged in the Bathysphere, she took dives of her own closer to the surface, clad in sneakers, a red bathing suit, and the era’s cutting-edge aquanaut equipment, which a mere century later appears to us as a specimen from the Atlantis of time, as exotic as Lancelot’s armor. (Being an artist above all else, she actually preferred the shallower waters, as she found that below 25 feet the world lost much of its color, particularly the fiery reds and oranges she so loved — those longer-wavelength colors easiest for water molecules to absorb and snatch from human eyes, leaving only glimmers of the shortest-wave blues and purples in the deep ocean.)

Writing with ravishing poetry of sentiment, in a language not her native, Bostelmann described her rapturous first encounter with what she called the “submarine fairyland,” into which she descended from a rickety forty-foot metal ladder with a sixteen-pound copper diving helmet pressing down on her shoulders:

I felt suddenly suspended in a maze of turquoise-green color as I swayed uncertainly back and forth on the ladder… Through the glass window of the helmet, I still saw the coastline with its white sand, its leaning cedars, and its little houses among which was my island home. However, the ripples on the water surface had caused them to be distorted. Slowly and hesitantly I started to fall, excited by the prospect of the great unknown.

She was about ten feet from the ground when a sharp, sudden pain hit her ears. But as she looked around, the wonder of it all — “a magnificent valley with peaks of tall coral reefs, swaying sea-plumes, slender gorgonians, purple sea-fans” — dissolved any awareness of the pain, and down she went, until her feet touched “the softest, whitest sand imaginable in which the gentle current had designed symmetrical ripples.”

It was her turn. She was six feet above the surface, which is only about the height and width of a two-story home, but a whole world away. Hers was the magical realism of reality’s magic, the origami of time, folding past and future into a single form of absolute aliveness:

I had descended to fairyland… I felt as though I were viewing a grand stage setting. The absolute brightness at these levels was broken by vertical sunbeams. As I gazed upon amazing coral formations, my attention was drawn to them. These shadowy shapes, which were only a very short distance away, formed columns and castles that had no known architecture. The bridges I saw were sea-plumes bent over; the slender corals that grew in the distance looked like towers. Everywhere absolute stillness — yet ceaseless activity. These formations can be attributed to tiny, living colonies that have built their coral homes one after another for untold centuries.

Else Bostelmann started to draw his own life.

On her first dive, she took a small zinc engraver’s plate with a steel pencil attached to it, hoping to record the rough contours of the life-forms she saw. This quickly proved a doomed endeavor — she could barely bend her head without losing her air supply, and the underwater pressure made her hands move at glacial speed as she attempted to drag the pencil over the plate.

Next, with the science-informed confidence that oil paint would retain both its consistency and its brilliancy because it couldn’t mix with water, she tried taking real paint and brushes down below — tying her paintbrushes to one handle of a wash-tub, squeezing paint colors on its bottom as if it were a palette, and tying a string to the other handle to drag the entire contraption behind her as she dove with the canvas under her other arm.

This, too, ended up “quite amusing” a flop: First, she realized she could only paint by laying her supplies onto the ocean floor and awkwardly kneeling over them; then, reaching for the blue paint but dipping her paint in the green, she realized that her human eyes were not adapted to judging even these most proximate distances accurately underwater; finally, upon reaching back to the palette for the correct color, she realized that in her discombobulation, she had forgotten to tie it and the current had carried it away.

However, she persevered. She finally found the right underwater studio setting after many attempts and many dives. After filling her palette with rainbow colors and adding lead to it, she attached her paintbrushes to the canvas and enjoyed watching the wooden handles floating in the gentle current.

With this improbable and inventive system, Bostelmann captured the essential form and color of what she saw, which she then developed in finer detail at her surface studio, managing thus to “record correct colors of unbelievable charm from some of Nature’s grandest compositions.” Nothing like it had been attempted before, and nothing like it has been accomplished since.

By the end of the 1930s — a decade that marked a Copernican revolution in our understanding of life in the bluest regions of our pale blue dot — Bostelmann wrote of the submarine fairyland she had rendered real and rapturous for the oversea world:

For a long time, all this beauty and wonder of shallow water, as well the mysterious depths, was unknown. It is now possible to use it and make it part of daily life.

[…]

The luxury and peace of the nether world of the sea is unmatched by anything in the higher realms. It is a modern adventure that can’t compare to the joy and wonder of discovering its incredible grandeur.

Complete the conversation with Edith Clements (pioneering plant ecologist), who did the same for mountain flowers as Bostelmann for undersea fauna. Then, revisit Ernst Haeckel’s extraordinary story on how he transformed his own tragedy into transcendent art by studying jellyfish in his visually stunning studies. Environment.

Donating = Loving

Over the past decade, I spent hundreds of hours writing and thousands of dollars each monthly. MarginalianIt was known for the infuriating name Brain Pickings its first 15 years. The site has survived despite being ad-free, and thanks to readers’ patronage it is still free. I have no staff, no interns, no assistant — a thoroughly one-woman labor of love that is also my life and my livelihood. Donations are a great way to make your life better. Every dollar counts.

Newsletter

MarginalianGet a weekly, free newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s most inspiring reading. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.